European Influence

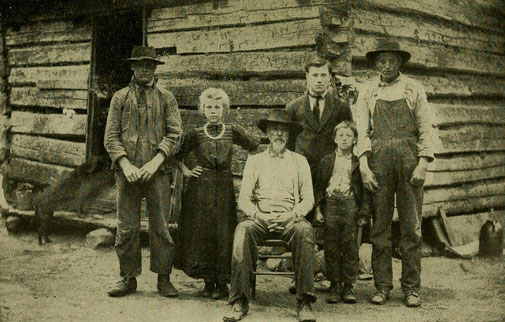

Terms like “bluegrass,” “country,” “mountain music,” “hillbilly” are some of the traditional associations that tend to refer to the Appalachian people (Zolten 2003). During the 18th and early 19th centuries, immigrants from England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales gave up their European homes to settle in the Appalachians. Because most settlements were rather new and did not average more than three generations back, they created tightly knit communities of people who were also isolated geographically (McClatchy 2000). People were forced to rely on each other for social, economic and religious connections. Among such connections were musical traditions passed down from generation to generation that were influential in remembering the past (McClatchy 2000).

The style of unaccompanied singing, such as an American ballad, “Pretty Saro”, was popular throughout the Appalachians when original researchers published their collections of Anglo-Celtic songs and English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians (Sharp 1952).

Cecil Sharp, a renowned folklorist with a sudden passion to preserve traditional country songs and dances that were then dying out in England, came to America in 1916 to find the ancient songs and ballads among early British settlers in Southern Appalachia (Langrall 1986). He found the Appalachian songs to have “a force and ethereal intensity that the mellow British versions often lacked” (Langrall 1986). Cecil Sharp underwent severe criticism due to the fact that he was specificially looking for remnants of English culture thus overlooking African-American communities (Thompson 2006).

Cecil Sharp's ballad collecting experience may highlight the importance of understanding one's role as an observer of folklore, and why studying any form of performance art helps us see people as one with the folklore they share (Martha and Stephens 2011). It is essential for the folklorist to not impose personal interpretations but place emphasis on collaborative interpretation or reciprocal ethnography (Martha and Stephens 2011). Folk music is a form of folklore that can form and express group identity and can unite different cultures under the realm of one folklore genre.

Despite his efforts, Cecil Sharp failed to catch the slurs and twangy gutturals of the traditional folk singers (Langrall 1986). They sang unaccompanied in a "high, lonesome" voice reminiscent of the fiddle's sound (Langrall 1986). Traditional ballad singers sang at home alone about the tales of love, history and the supernatural unlike the singers after the 1920’s who became performers singing in front of large public. They were the first professional entertainers who would eventually end up in Nashville (Langrall 1986). By the 1930th, country music could be heard on radio all over the country. Appalachian Folk Music rapidly went from its bucolic roots to Nashville stage.

Unlike other European migrants, until a few years ago, there had not been much investigation and scholarship looking at the German connections (Hadamer 2010). Scholars now agree that aside from Scottish and English, German-speaking settlers played a role in the contributions to folk music in Appalachia. One of the small towns in West Virginia was founded in 1869 by German and Swiss settlers who brought their guitars, fiddlers and accordions (Hadamer 2010). Fiddle tunes like the Shepherd’s Wife Waltz still get linked to a German or Swiss background. It is now believed that the hammered dulcimer had also arrived to the Appalachia with German-speaking settlers in the 1700s, whereas, the modern day Appalachian dulcimer had been owned by Mennonite pioneers and was primarily used to accompany private hymn singing (Hadamer 2010).

You can do it, too! Sign up for free now at https://www.jimdo.com