African-American Influence

"You Got Soul, If You Didn't, You Wouldn't Be in Here..."

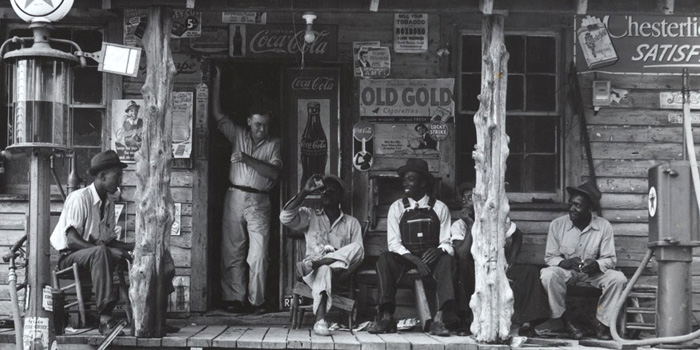

In spite of the presence and influence of African-American communities and other people of color, Appalachia has often been represented as being overwhelmingly white (Thompson 2006). From 1820 to 1860, the population of African-Americans in the region ranged from 15.1 to 19.5 percent (Turner and Cabbell 1985).

One of the greatest influences on Appalachian music was that of the African-American (Hay 2003). With the expansion of the railroads to the area of southern Appalachia, native Appalachians met African-American section workers who laid track. They brought with them the guitar and banjo, which became ideal for the accompaniment of singing and dancing (Langrall 1986). Free blacks and black slaves were present throughout the Appalachian region due to the region’s significance in slave trading into the deep South (Dunaway, 2003). The term Affrilachian, coined in the 1990’s by poet Frank Walker, refers to African-American migrants in the region of Appalachia. (Walker, 2000).

However, the music of African-Americans in the Appalachian region has been poorly documented and rarely acknowledged when referring to Appalachian music (Hay 2003). J. C. Staggers (1899-1984), known as the best banjo player, black or white, is reluctantly given recognition in the Appalachian music legacy (Hay 2003). The lack of identifiable region wide styles has reinforced disregard for black Appalachian music. Moreover, the commercial record companies ignored black Appalachian musicians, therefore, continuing to perpetuate the notion of "invisibility" (Hay 2003). Black music of nearly every genre found its roots in the mountains of Appalachia and impacted the country’s and the world’s music (Pearson 2003; Hay 2003). Despite the recent scholarship highlighting the African-American influence in Appalachia, many still refuse to accept the music of African Appalachians as Appalachian music (Hay 2003). Just like Apache storytellers’ symbolic connection to the place names among mountains and arroyos (Basso 1984), the African-American people of Appalachia are not forgetting the emblematic power of the Appalachian foothills that gave rise to the many genres of folk music.

The Banjo

The banjo, an African American instrument originated in Africa and was introduced into the Southern Appalachians in the early to mid-nineteenth century. It became a staple of mountain dance music as well as later music genres, such as bluegrass (Conway and Odell 1998). There was cultural interchange between blacks and whites however; African-Americans adopted the European fiddle, whereas European Americans began playing the African banjo (Thompson 2006). The combination of fiddle and banjo became common in the mid-19thcentury although it was noted as early as the 1770s. (Conway 1995). The drum was the original accompaniment for the banjo before it was banned during slavery throughout most of the South due to the fears of a slave rebellion being communicated through drums (Thompson 2006).

The Ballad of "John Henry"

“John Henry” is one of the most important and widely-known African-American ballads that finds its original roots in oral tradition (Tullos 2004). It is possible that the legend would not have survived on paper only or if it had been burdened with documentary detail (Tullos 2004). In fact, many linguistic anthropologists acknowledge the capacity of musicality as a method of suppressing intertextual gaps (Gross 2001). The legend depicts a hero whose martyrdom symbolized the tension between manual labor and the industrial revolution from which there was no redemption (Tullos 2004).

You can do it, too! Sign up for free now at https://www.jimdo.com